A first-of-its-kind gene therapy dramatically reduced misfolded protein levels in some clinical trial participants for up to six months and reduced levels in all participants for up to a year.

Researchers successfully disabled a gene in human patients by treating them with CRISPR gene editing technology, clearing patients’ blood of a toxic protein for some patients by as much as 93 percent up to six months after the initial treatment. The researchers detailed the findings in a press release, a phase 1 clinical trial update, and data slides on Monday (February 28).

“It is quite remarkable that this first [intravenous] CRISPR-based gene-editing effort has been so successful,” gene therapy researcher Terence Flotte of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, who was not involved with the study, tells Science. “This demonstrates great potential for the power of this platform clinically.”

See “CRISPR Inches Toward the Clinic”

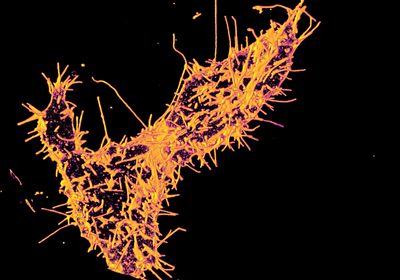

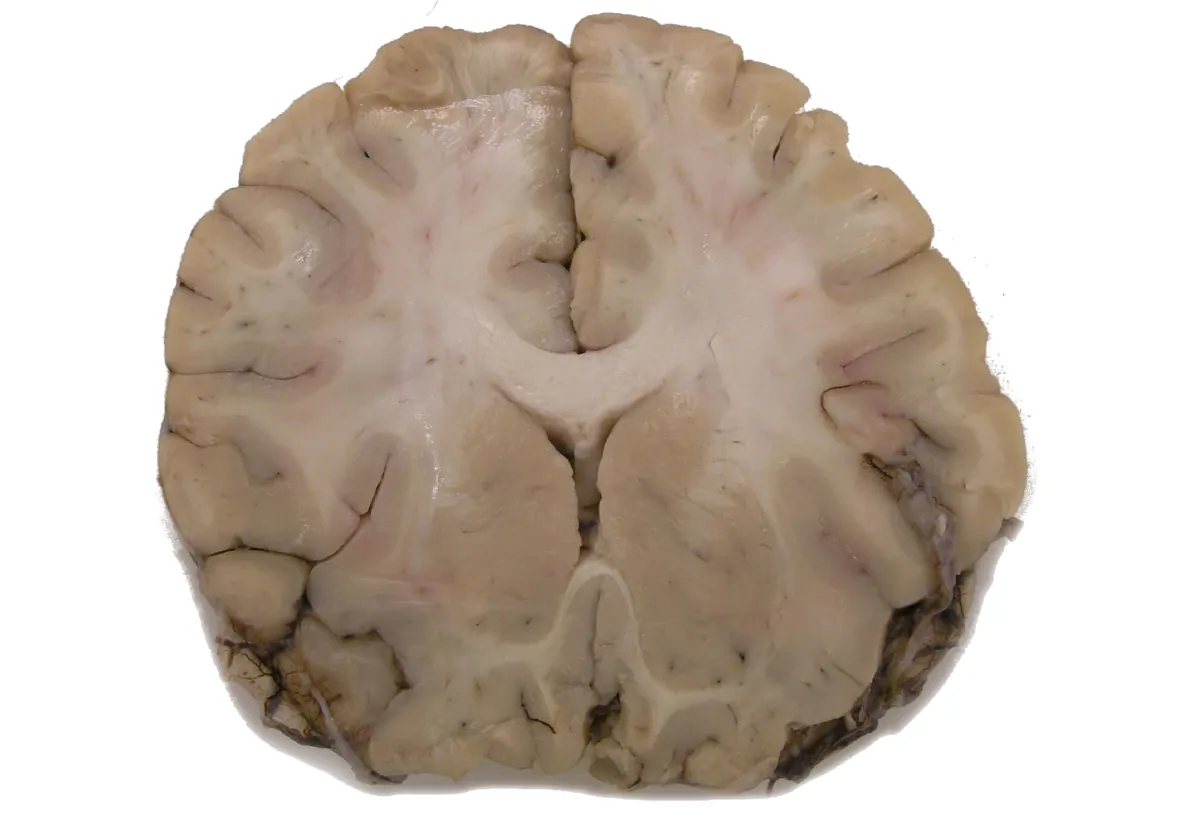

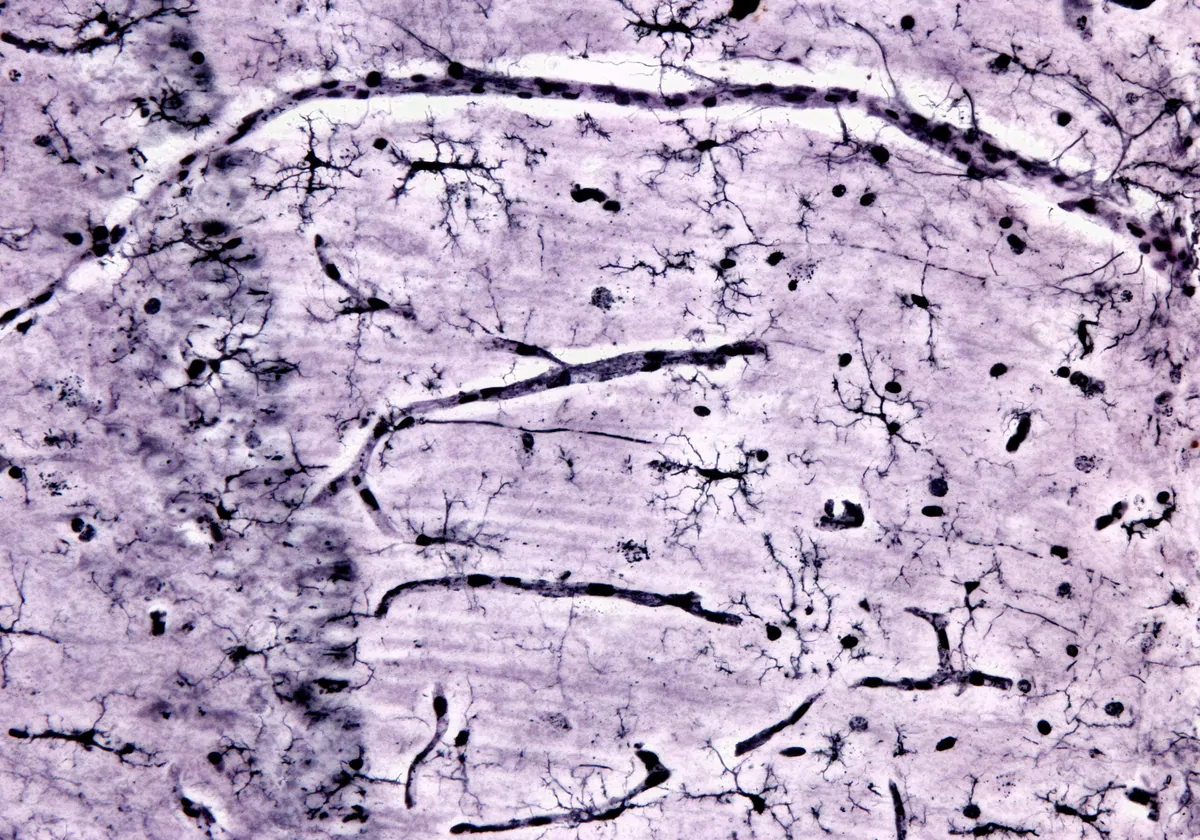

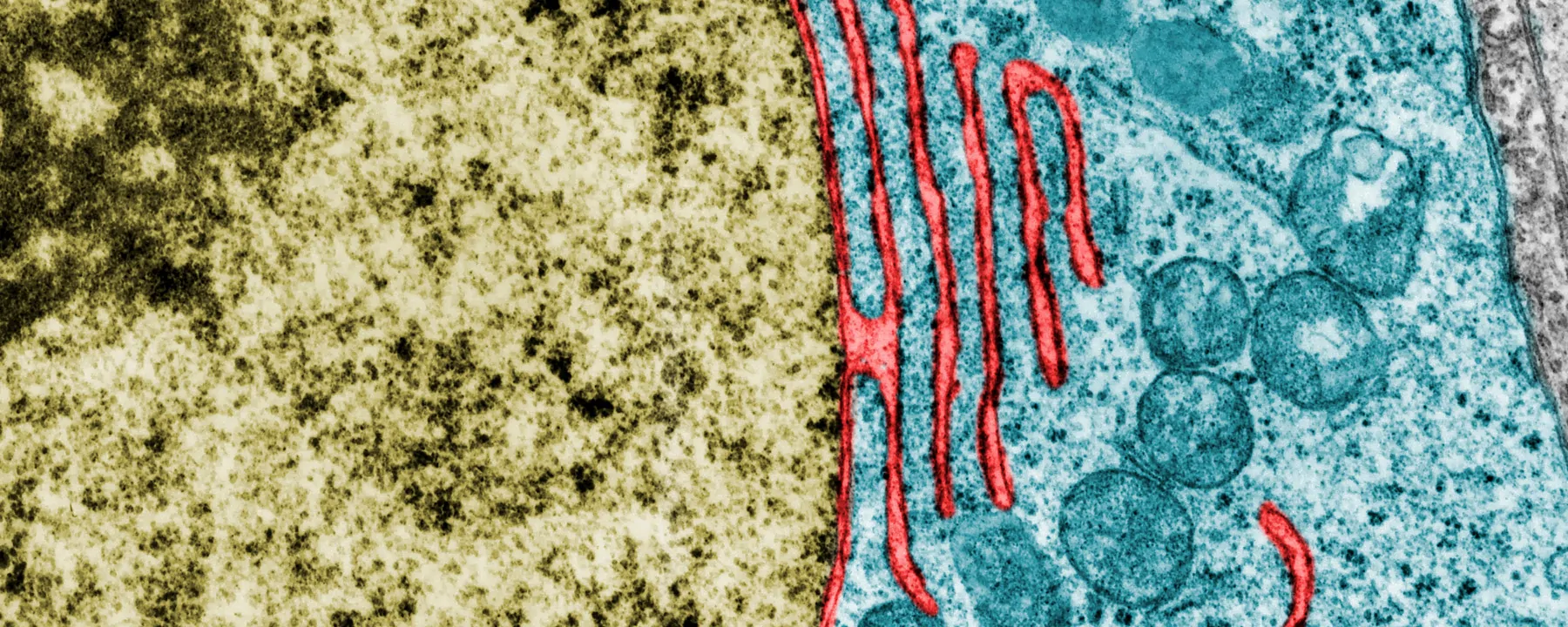

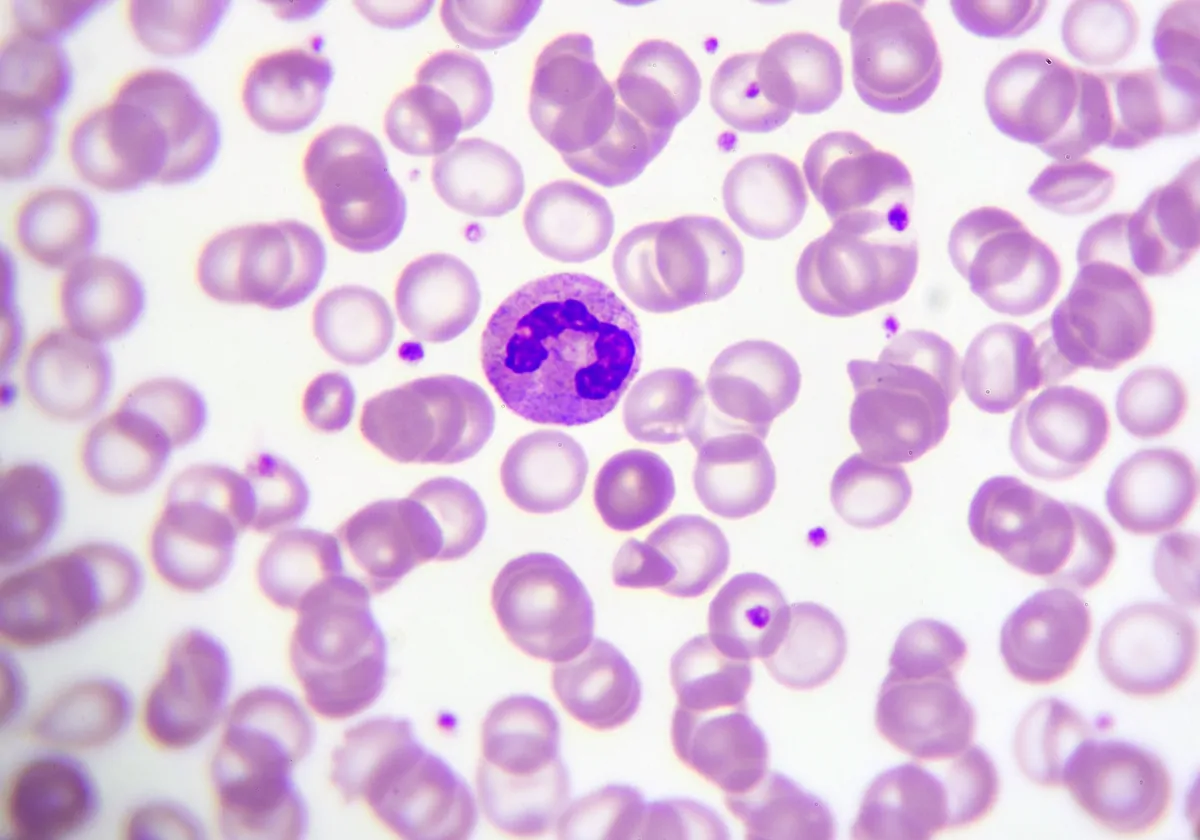

The 15 patients, who are enrolled in a clinical trial conducted by the pharmaceutical companies Intellia Therapeutics and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, have an inherited gene mutation called transthyretin (TTR) amyloidosis, a progressive neurological disease that causes numbness, nerve pain, and heart failure. The mutation causes the liver to produce a misfolded version of the protein transthyretin that clumps together into insoluble amyloid fibrils that the body cannot clear. These build up in the heart, muscles, internal organs, and nerves, causing damage and preventing normal function. Healthy transthyretin helps transport vitamin A (retinol) throughout the body but has a “limited and specific normal function,” which means that knocking it out has limited physiological effects, according to the clinical trial, which was published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The researchers behind the trial tell Science that they hope their CRISPR-based treatment will be the first single-dose treatment for TTR and confer long-lasting benefits. By contrast, existing treatments must be administered regularly. Alnylam Pharmaceuticals’ Onpattro must be administered once every three weeks to provide therapeutic benefits. Ionis Pharmaceuticals’ Tegsedi must be administered every week.

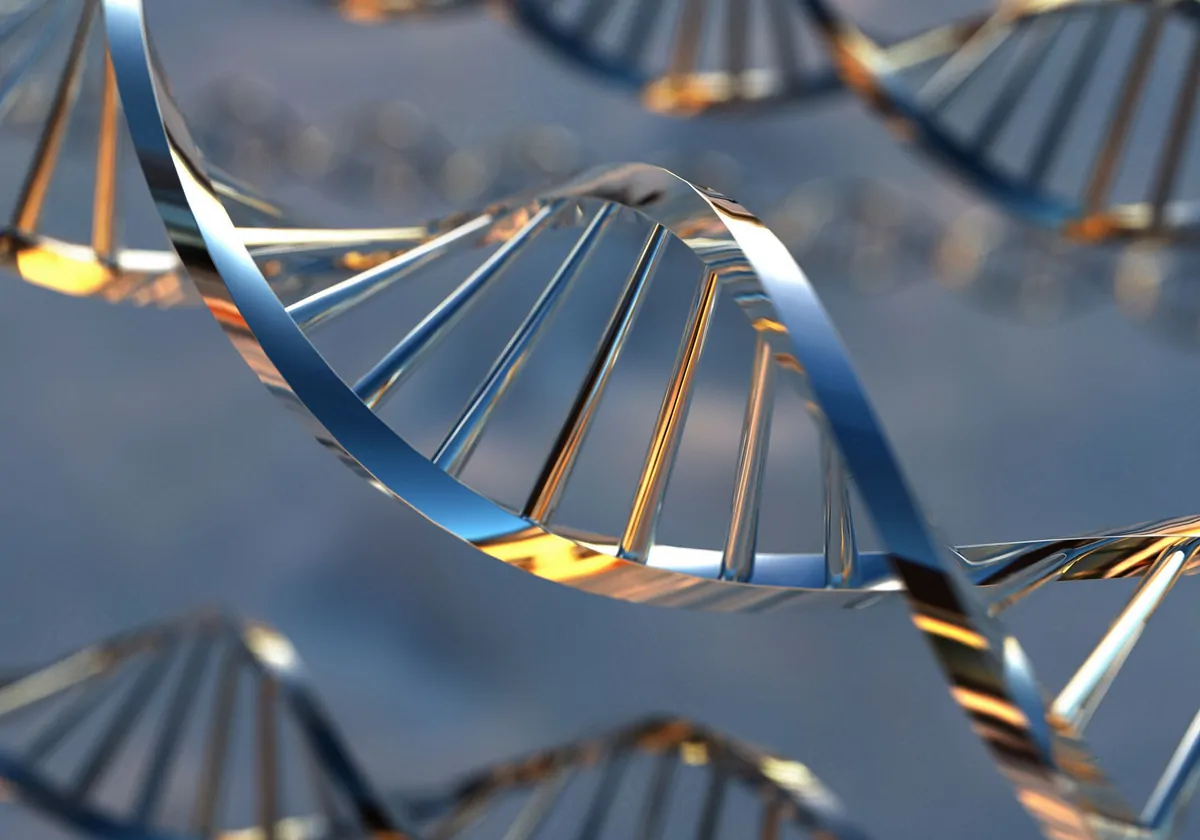

Last year, Intellia and Regeneron started injecting patients with a CRISPR-Cas9 system, encased in fat droplets, that contained genetic instructions to remove the dysfunctional TTR gene from cells, reports Science. The droplets contain a guide RNA that targets the gene that produces TTR, and another RNA strand that guides the gene-cleaving Cas9 to liver cells. After the Cas9 protein cuts the portion of DNA that encodes TTR, the body’s native gene repair system glues the DNA back together, but it does so imperfectly, truncating and disabling the TTR gene.

At that time, the pharmaceutical companies reported that the blood levels of the protein dropped dramatically in six patients one month after injection. However, there was no documented improvement in the patient’s symptoms.

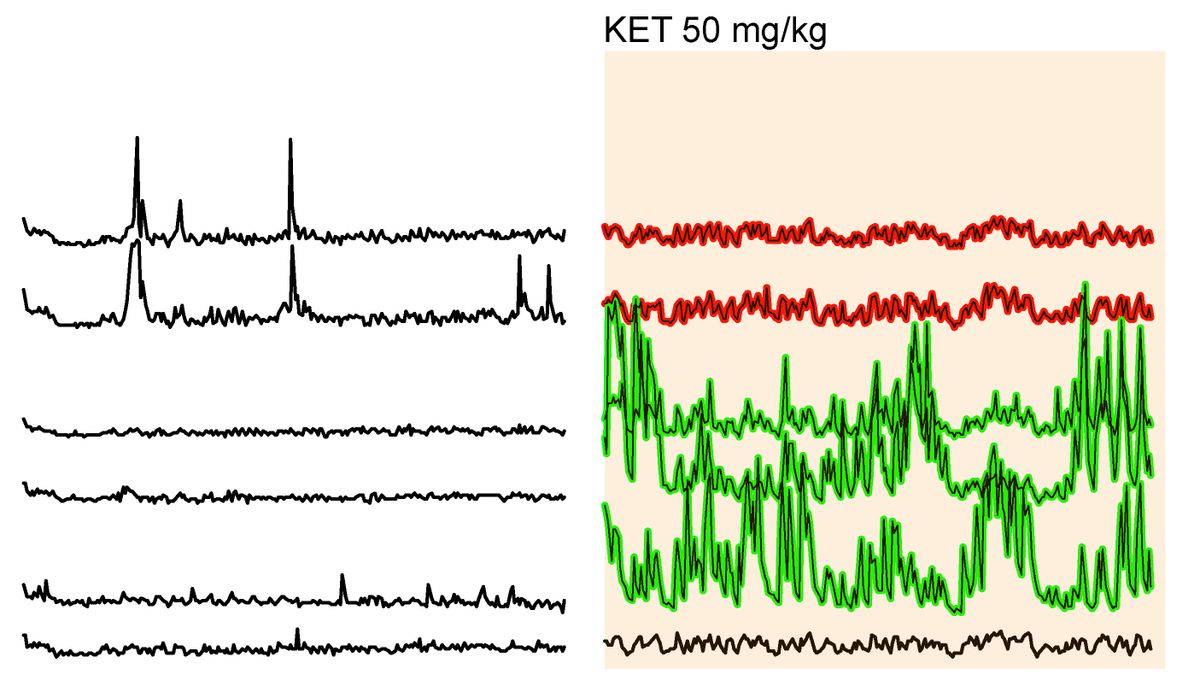

Since publishing the initial report, the researchers have added nine more participants to their ongoing clinical trial. Patients received one of four doses of the treatment. The researchers now report that TTR levels in patients who receive a single treatment remained stable—at 7 to 59 percent of pretrial levels 2 to 12 months after treatment—with individual patients varying depending on which doses of the CRISPR treatment they received. The patients that received the highest dose saw a 93 percent reduction in TTR levels one month after treatment, which remained stable at least six months after treatment. The researchers reported that patients that received the lowest dose, the six patients in the initial cohort, initially saw a 52 percent reduction in protein levels, but this number dropped to 41 percent after a year. The researchers also reported no severe side effects with any doses. However, The Washington Post reports that more data are needed to show that the treatment will not have any dangerous side effects or cause off-target DNA damage down the road.

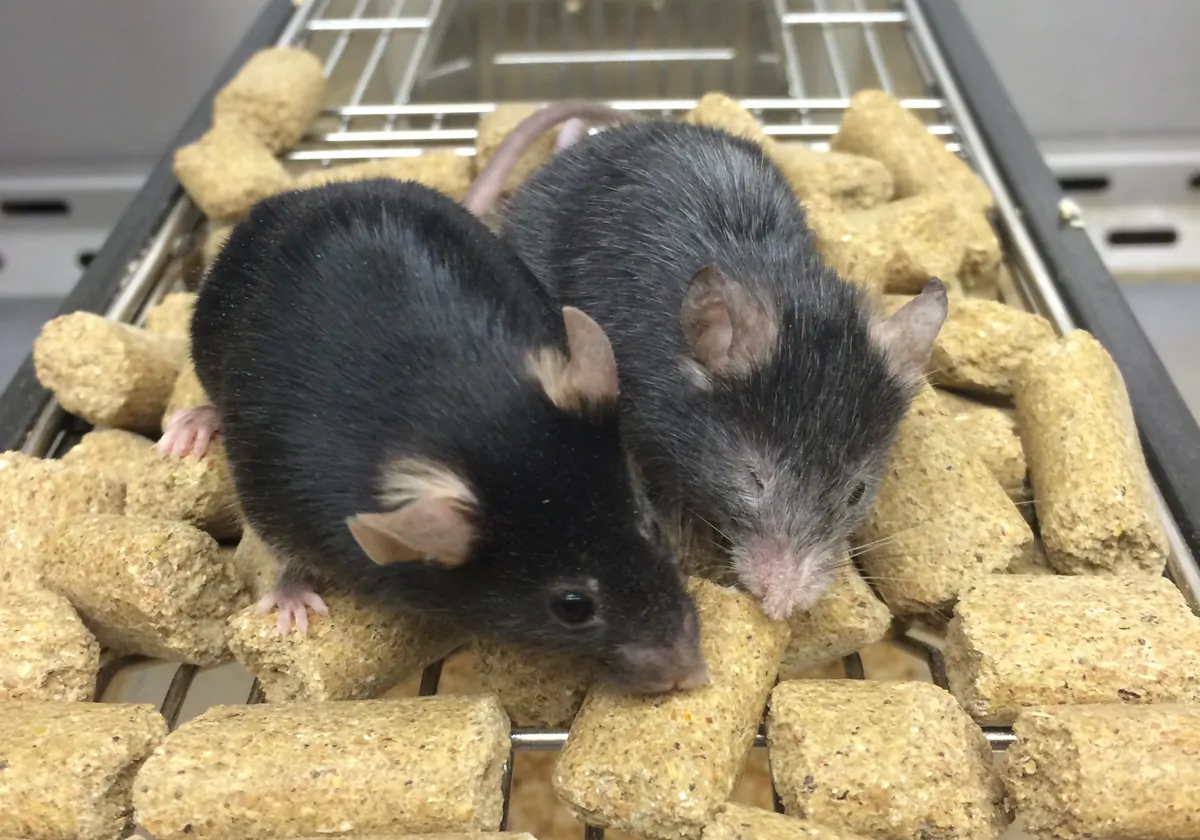

Based on preclinical trials in mice and monkeys, the researchers expected protein levels to remain low in humans. However, liver cells are replaced every 200 to 300 days, so there’s a chance that the patients’ livers once more begin producing misfolded TTR.

See “First Patient Receives In Vivo CRISPR Editing”

The researchers are unsure whether the treatment will improve symptoms or simply halt disease progression. So far, the researchers haven’t collected data on whether the patients, who were already experiencing pain and numbness throughout the body before treatment, have experienced a reduction of symptoms. However, the researchers remain optimistic, as the drugs currently in use for TTR amyloidosis do improve symptoms despite only decreasing blood TTR levels to 80 percent of normal.

Correction (March 4): The article has been updated to reflect that trial updates were released February 28, not March 1. The article has also been updated to reflect that the researchers have not yet reported clinical outcomes. The article has been clarified to reflect that Intellia updated an ongoing clinical trial, in which researchers first published that it was possible to disable a disease-causing gene through a single infusion of a CRISPR-based therapy last year, with new data. The Scientist regrets the errors.