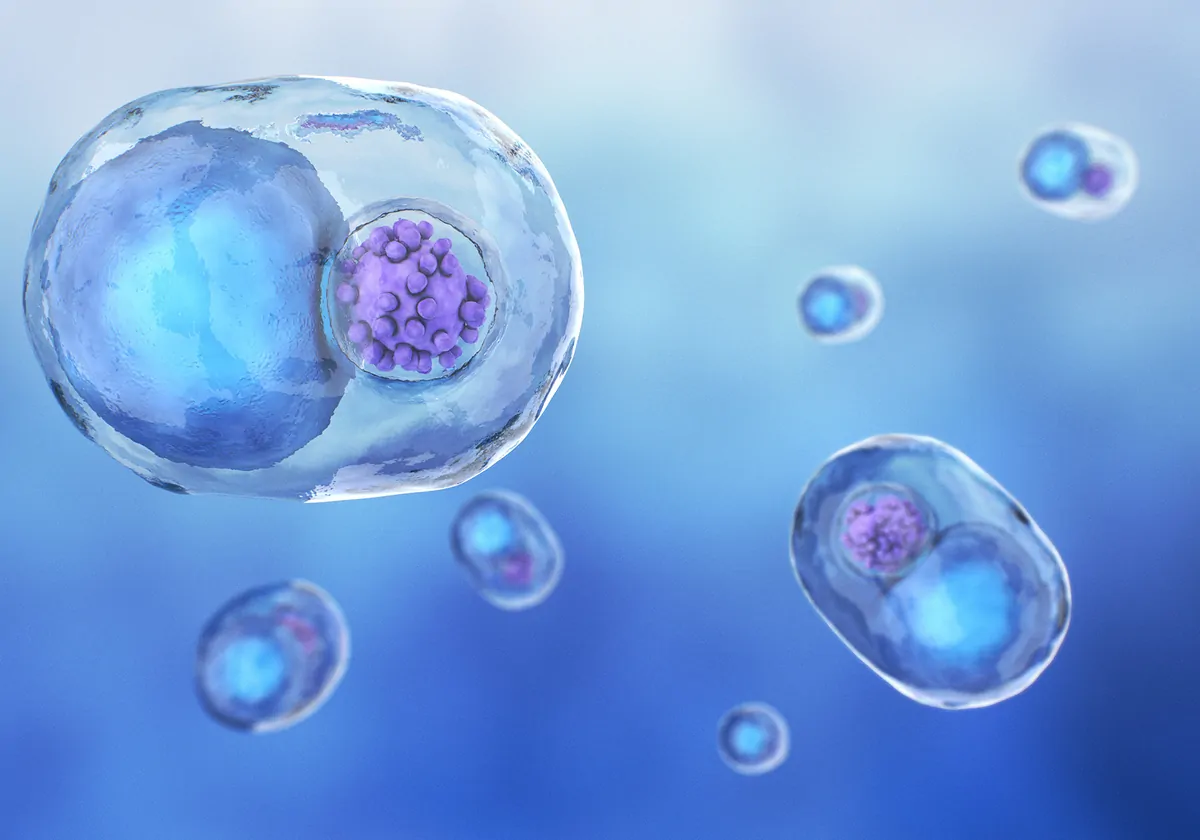

Scientists have developed a new line of stem cells—all derived from the same person—that can be used to study sex differences without the confounds of interpersonal genetic differences.

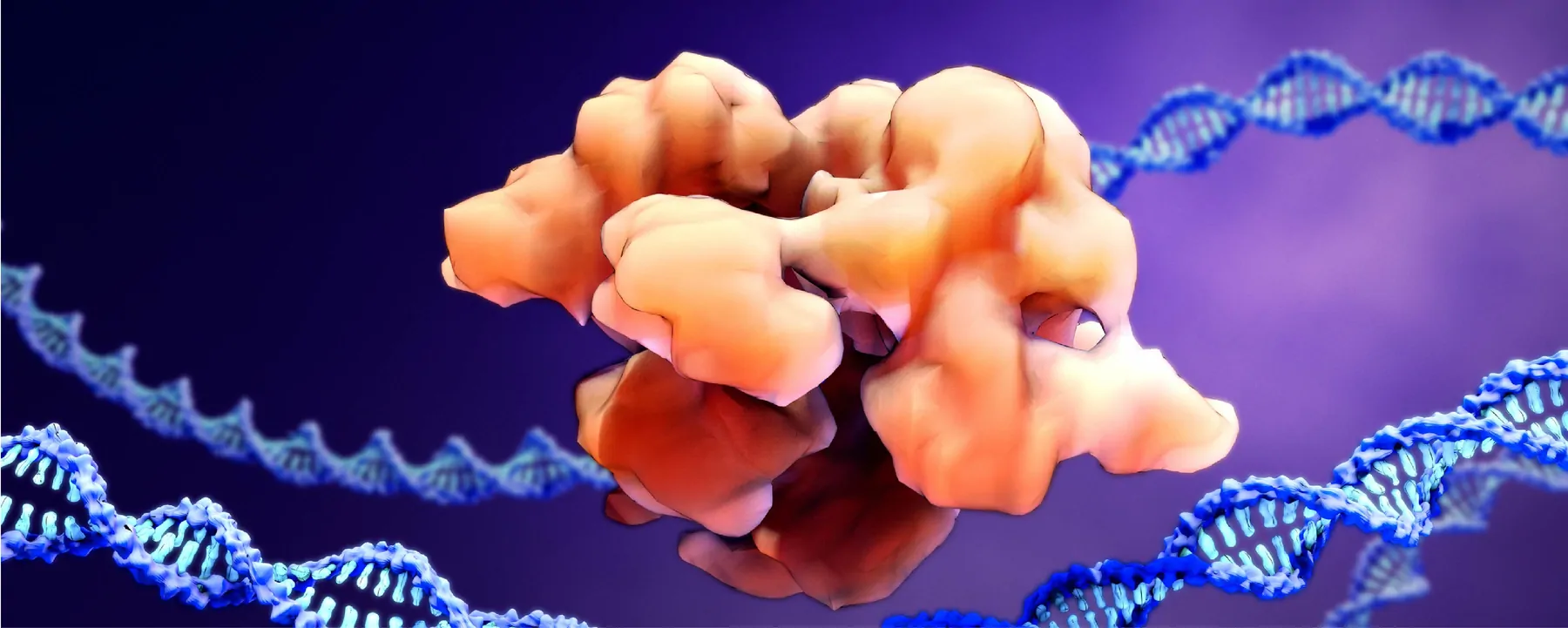

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), which are cells taken from a person that are then reprogrammed to abandon their current roles and return to a stem cell–like state, have become valuable tools not only for therapeutic purposes but also for probing the genetic mechanisms underlying cell behavior and disease. However, findings drawn from stem cell studies may not be broadly applicable, as the fact that all cells in a given line share the same genetic sequence makes it difficult to generalize discoveries, especially when it comes to investigating potential sex differences.

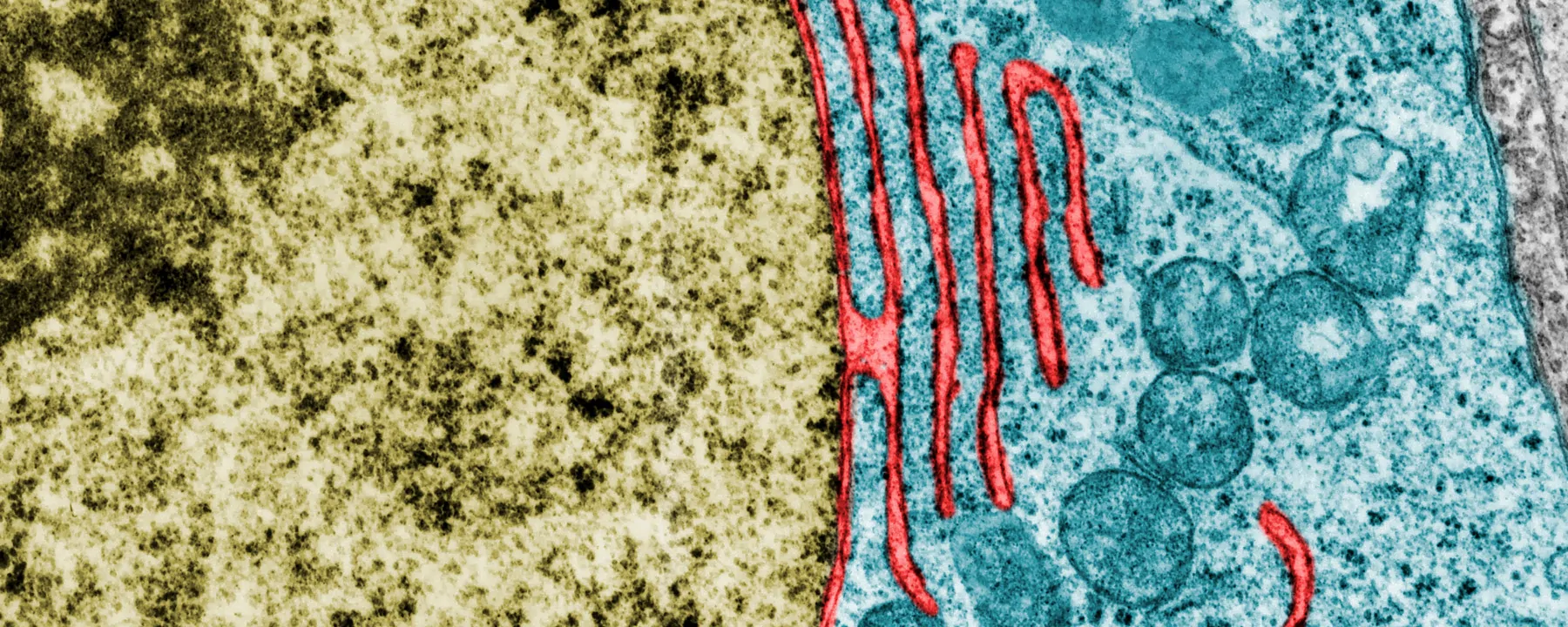

See “Sex Differences in Immune Responses to Viral Infection”

That’s why a team of scientists led by Benjamin Reubinoff, an embryonic stem cell researcher at the Hadassah Medical Organization in Jerusalem, and MD-PhD student Ithai Waldhorn set out to create a new platform for studying genetic sex differences. As Reubinoff tells The Scientist, “The origin was really to generate a model for studying sex differences, given the limitation of the current studies which are based on larger cohorts, or comparing males to females, or using multiple cell lines. There was, he says, a need for “a simple model that can overcome the masking of genetic variability between individuals.”

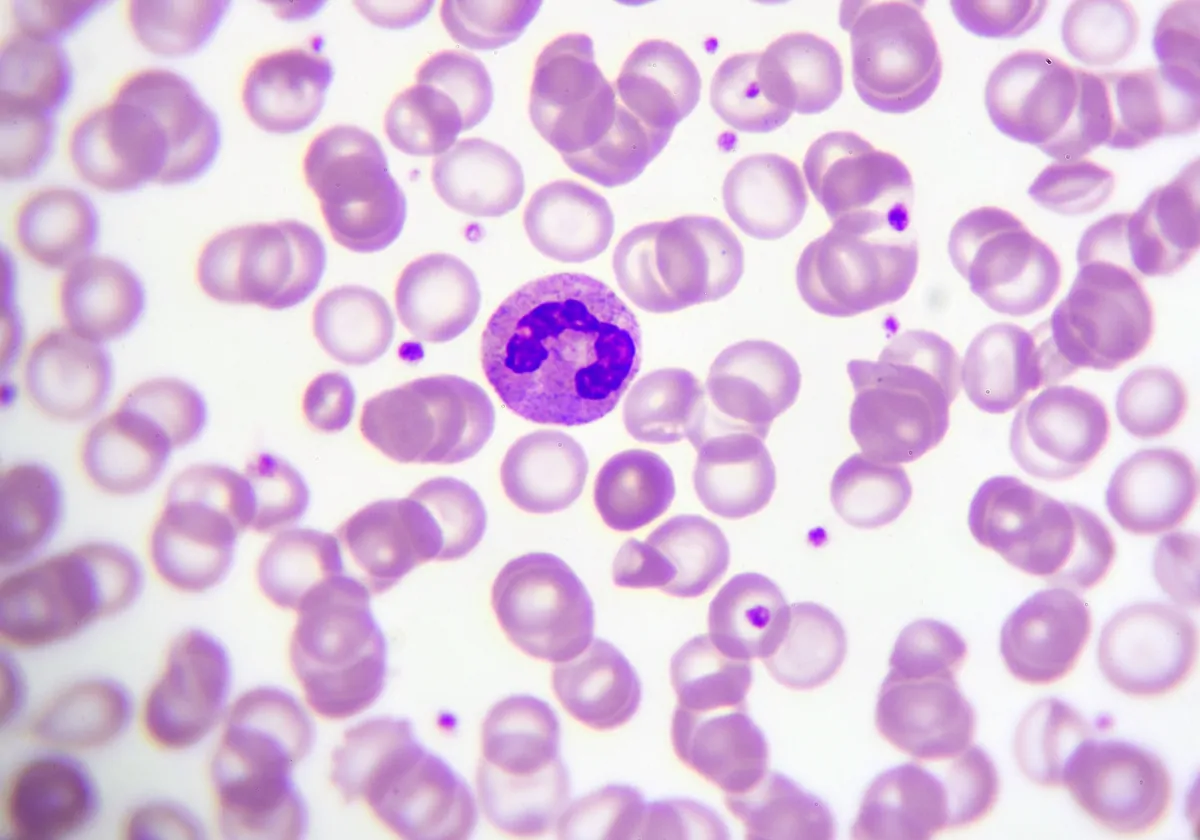

To develop such a model, the team obtained cells from a repository that had been taken from someone with an unusual case of Klinefelter syndrome, a rare genetic condition that affects roughly 1 in 500 boys in which they’re born with an extra copy of the X chromosome, resulting in an XXY genetic makeup. What made this person even more unusual—and ideal for Reubinoff’s vision—is that, in addition to the 47XXY cells characteristic of the condition, they also had a large number of 46XY cells, a phenomenon known as a mosaic phenotype. As the study, published on November 24 in Stem Cell Reports, describes, the variety of cells taken from the Klinefelter patient allowed the team to generate 46XX, 46XY, 45X0, and 47XXY hiPSCs that are otherwise genetically identical. This means that any observable differences among them—related, for example, to disease risk factors or response to a pharmaceutical—can almost definitely be attributed to genetic sex differences.

See “From Many, One”

“When you study individuals, and you compare males to females and you find differences, you cannot differentiate whether they stem from the chromosomal differences or hormonal differences,” Reubinoff explains. “This model is unique because it allows you to differentiate between chromosomal effects and hormonal effects.”

In hindsight, Reubinoff says he’s not sure why no one had thought to develop multiple sexes of stem cells from one person before, though it may have to do with the rarity of this particular form of Klinefelter. Mariana Argenziano, a stem cell biologist at Ncardia who works on generating stem cells for medical research and didn’t work on the study, shares similar thoughts.

“In this case the authors were lucky to encounter a case with a triple mosaicism 47,XXY/46,XY/46,XX, being able to isolate all sex backgrounds from the same patients, working with naturally isogenic cells,” Argenziano tells The Scientist in an email.

Argenziano adds that the study “was a very elegant and clean way of approaching” the problem of studying sex differences in stem cells. “Testing sex differences has been an issue in the field of stem cells,” she says. “It is not a secret that males and females respond in a different way, but the barrier of the different genetic backgrounds has always interfered with obtaining clean results and really understanding the effects of sex differences,” even when cells are taken from members of the same nuclear family.

See “Different Genes Influence Lifespan in Male and Female Mice”

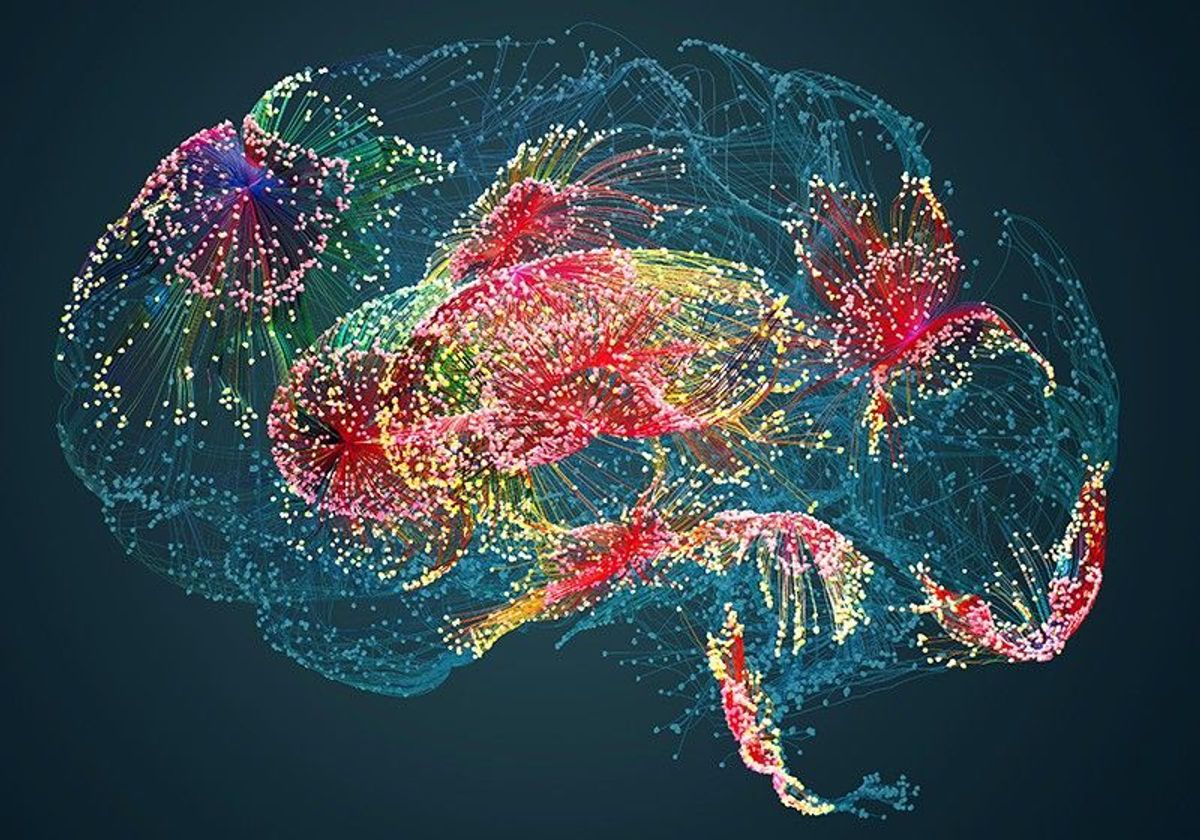

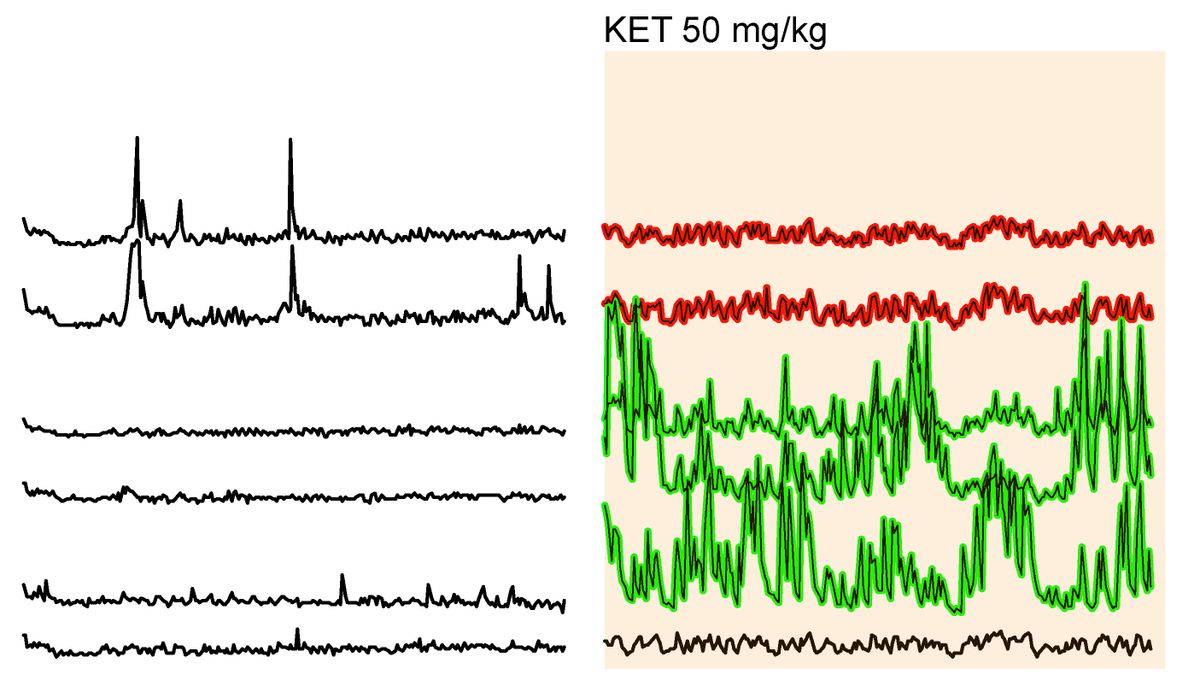

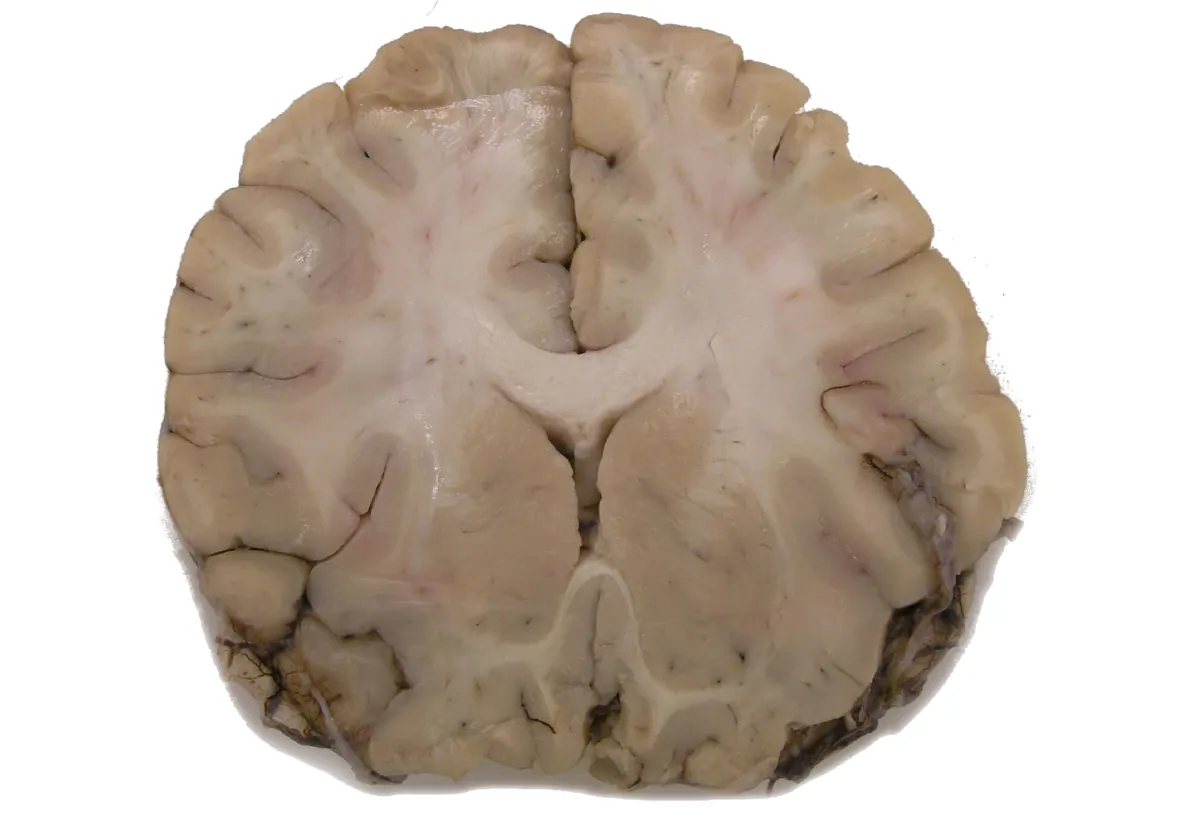

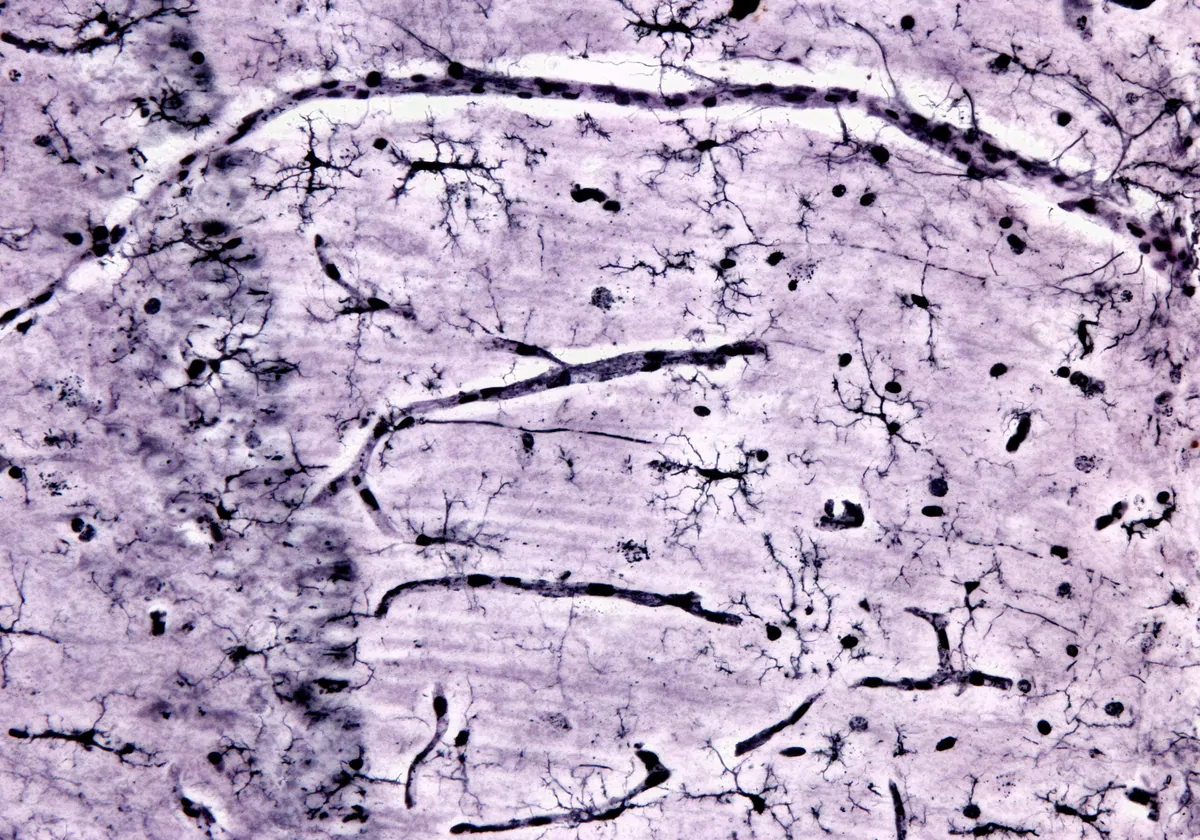

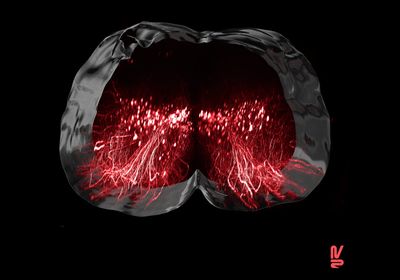

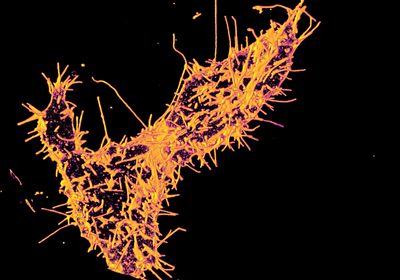

In the study, the authors explored a few potential uses for the stem cells, such as tracking sex differences in the earliest stages of neural development, investigating whether the presence of the Y or an extra X chromosome drove changes in gene expression, and demonstrating that the Y chromosome was linked to increased expression of schizophrenia–associated genes. Reubinoff says that his lab will continue to study early development, but that he hopes other researchers will expand on the platform to examine other aspects of chromosomal sex differences, especially disease progression and drug development. He says he was “very surprised and very excited” to see that his platform yielded results that agreed with existing cohort studies, which he sees as verification of the model.

“I can see a lot of potential for these cells,” says Argenziano. “Drug testing is another main field where these cells can add a lot of value. Many pharmaceutical companies have established the use of stem cell-derived models in their compound testing, and differences between males and females is yet to be addressed.”

Reubinoff concedes that the fact that the cells all stem from one person is a limitation, but says this could be addressed by generating similar lines from other mosaic Klinefelter samples. “I would say it would be nice to have more similar lines from more genetic backgrounds,” he says, “to be able to confirm results.”